A question of institutions?

This year's Nobel Prize winners in economics show the influence of institutions on a country's prosperity. The three prizewinners have close ties to the University of Zurich, as UBS Foundation Professors David Hémous and Florian Scheuer outline in their article for 'Die Volkswirtschaft', an economic policy magazine by the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO).

This article by David Hémous and Florian Scheuer was originally published in 'Die Volkswirtschaft' on 8 November 2024 in German. Translated and edited for layout purposes by the UBS Center.

Adjusted for purchasing power, per capita income in Switzerland is 75 times higher than in the Democratic Republic of Congo, one of the poorest countries in the world. How can such extreme differences in prosperity levels be explained? And why is the economy of some countries growing while elsewhere it is stagnating or even shrinking? This question also occupied this year's winners of the “Alfred Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences”. In October 2024, the prize was awarded to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson (see box). These central questions have been occupying economics since the times of Adam Smith. As early as 1776, he was driven by these questions, to which he sought an answer in his magnum opus “The Wealth of Nations” 1. “Once you start thinking about it, it's hard to think about anything else,” said Robert Lucas, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1995. Traditionally, economics explains the different growth rates of countries by the fact that they invest different amounts in capital, education or technological innovation. This is because these investments boost the productivity of an economy and thus lead to higher income. However, this then raises another question: “Why” do some countries invest more than others? Or, in other words, what are the “fundamental” causes of economic growth?

Institutions or wealth: Which came first?

Douglas North, who won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences in 1993, had already argued that the answer lies in institutional differences between countries. Such institutions include, in particular, rules and laws that significantly influence the economic incentives of companies and households – for example, the guarantee of property rights, the independence of the judiciary, functioning markets, political stability, an efficient tax system and opportunities for social advancement. But this view was controversial at the time for two reasons. Firstly, because causality could actually work in the opposite direction, namely that economic development leads to the introduction of better institutions. And secondly, it was popularly believed that geographical factors were crucial for economic development. In 1998, for example, the scientist Jared Diamond put forward this view in his Pulitzer Prize-winning bestseller “Guns, Germs and Steel”. His theory emphasizes natural and geographical conditions such as soil quality, natural resources, topography, climatic conditions and diseases such as malaria. These in turn have an impact on agricultural productivity, transport costs and the accumulation of human capital, according to his thesis.

Nobel Prize winners solve the chicken-and-egg question

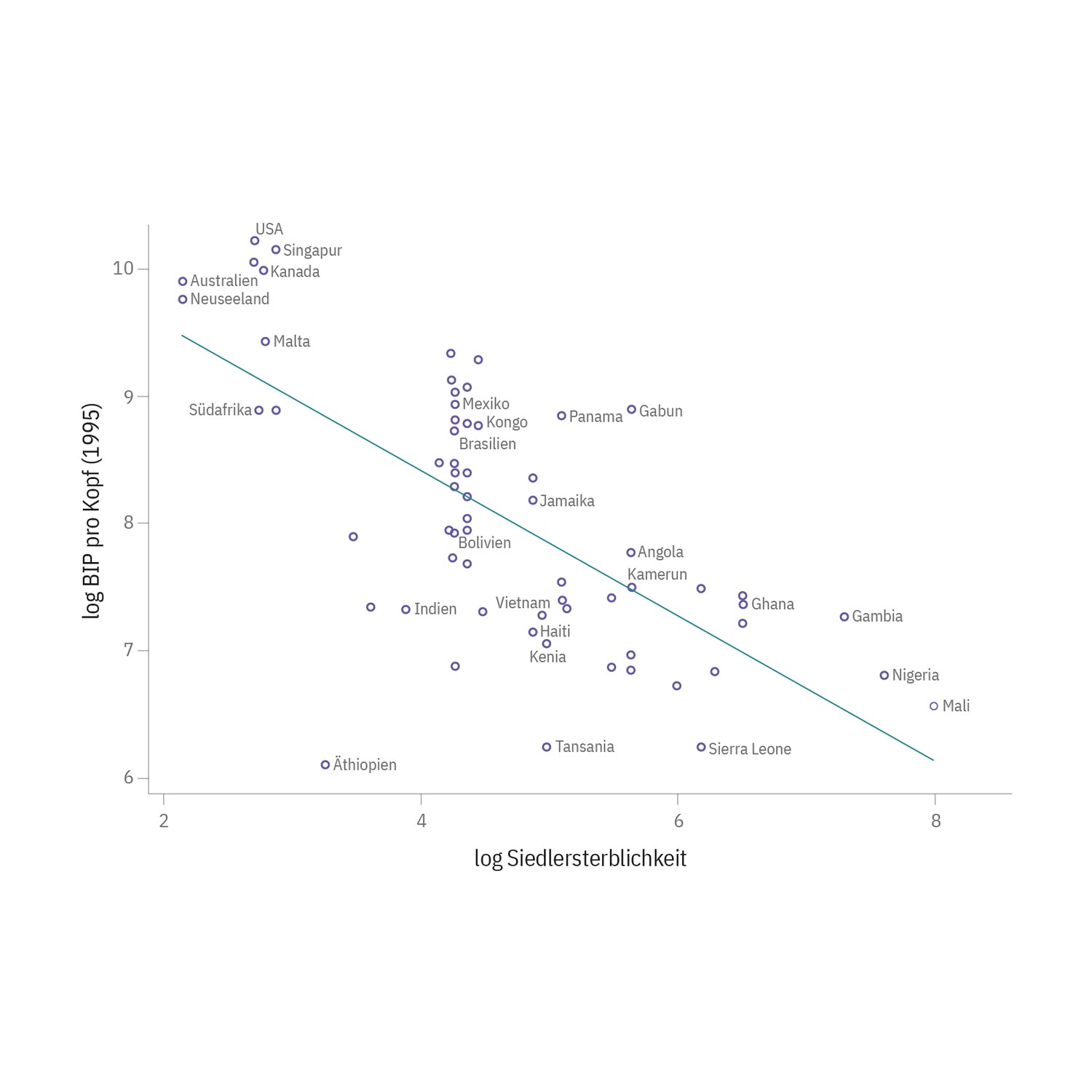

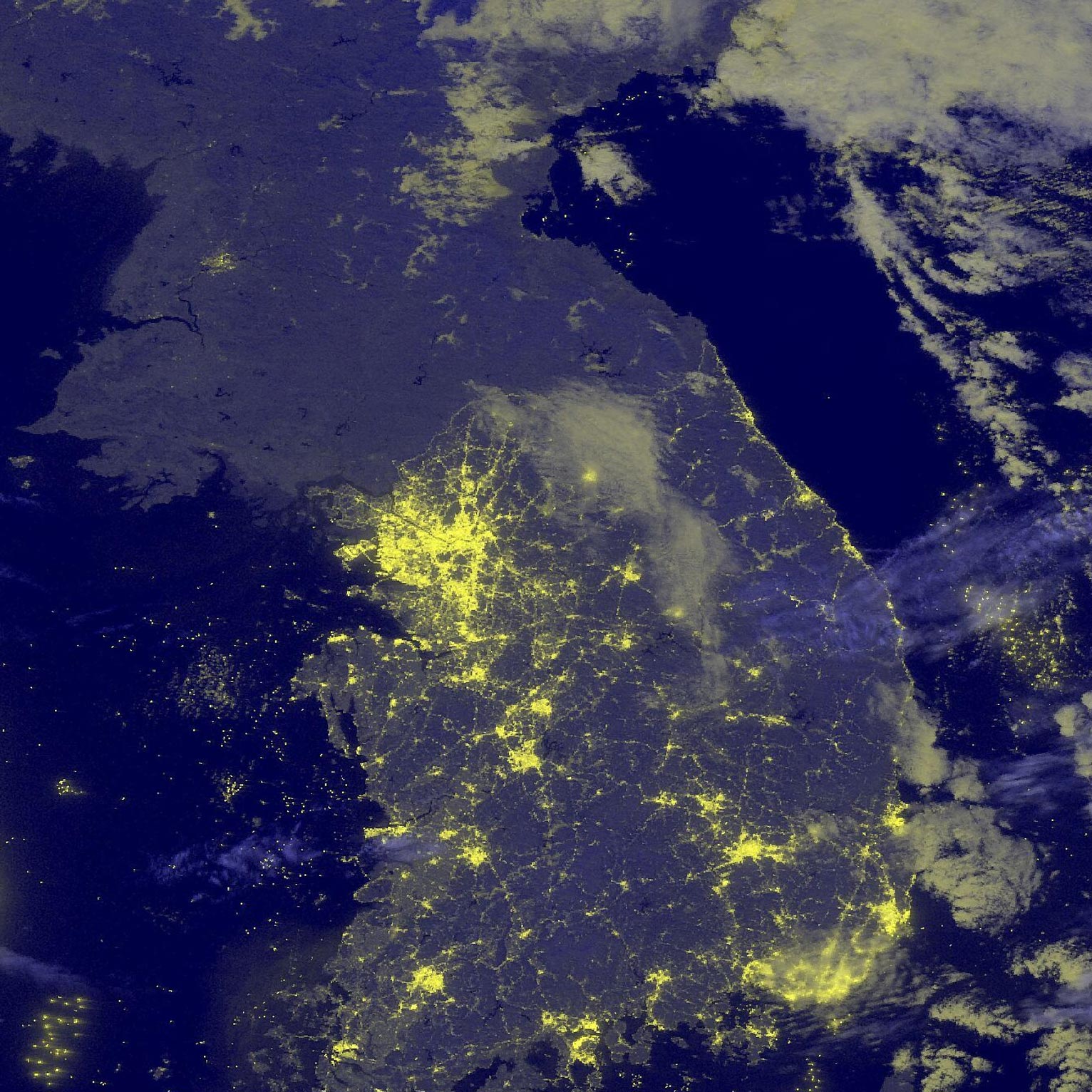

This is the starting point for the research of this year's Nobel Prize winners in economics. Starting with a sensational article in the American Economic Review in 2001, economists Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson presented causal evidence on the role of institutions in economic development. In addition, they have developed new theories in a series of research papers and books that can explain why inefficient institutions persist. They also defined conditions under which institutional reforms can take place. To break down the cause-and-effect relationship between institutions and economic development, the researchers delved into the archives of economic history. Specifically, they looked at the age of colonization between the 15th and 20th centuries, when European powers began to establish settlements on other continents. The researchers argued that where the mortality rate of the first settlers was high due to disease, the Europeans set up purely “extractive” institutions. These had the sole purpose of exploiting the available resources. In contrast, “integrative” institutions based on the European model were set up in places that offered better chances of survival. The aim was to establish a European population there. The United States is one example of this. From the beginning of colonization, the settlers there established relatively inclusive institutions for the time: the 13 colonies were fairly independent from London and had an elected representative assembly. However, there was one major difference: slavery was widespread in the South. While it allowed a small elite to amass considerable wealth in the plantation economy, it was at the expense of a large portion of the population. And because the established elite benefited from the status quo, slavery slowed down innovation and industrialization. By the mid-19th century, the South was considerably poorer than the North.

From poor to rich

Due to the longevity of such institutional differences, countries like Congo or Haiti, where there was initially a high mortality rate among settlers, are still poorer today (see figure). Empirical evidence also shows that this is the case even when the countries are geographically similar. In addition, there is what is known as the resource curse: natural resources often lead to extractive institutions, so that resource-rich countries like the American South or Haiti, which were relatively rich originally, ultimately developed less than initially poorer countries like the northern United States or Australia. Like the southern United States, Haiti was dependent on plantation agriculture and slavery, but unlike the southern United States, it had no inclusive institutions for a significant portion of its population. Although the country's GDP was comparatively very high at the end of the 18th century, it never developed further. By contrast, Switzerland is an example of a country that has benefited from inclusive institutions. It did not experience absolutism and gradually became more democratic, including through the introduction of direct democracy. Although Switzerland was not among the first countries in Western Europe to industrialize, it eventually became one of the richest. The work of this year's Nobel Prize winners has had a significant impact on research into fundamental questions of economic growth. In particular, they have promoted the linking of economic-historical analyses with models of political economy and growth theory. The conviction that institutions are crucial for economic development is now widespread and has also found its way into development policy.

Acemoglu's connections to Zurich

In particular, the Turkish-American economics professor Daron Acemoglu, who teaches at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the United States, had long been considered a candidate for the Nobel Prize in Economics. In addition to his Nobel Prize-winning work, he has published influential research in other areas of economics that could also have earned a Nobel Prize. For example, in his work on “directed technical change,” he explains under which circumstances the direction of technological progress tends to increase income inequality or favor dirty energy over clean energy. 2 Daron Acemoglu also has close ties to the Department of Economics at the University of Zurich. He has visited the department regularly, for example in 2012 for the opening of the UBS Center for Economics in Society. And he will be at the Department of Economics at the University of Zurich on January 29 to present his latest book, “Power and Progress,” in a lecture. Last but not least, we also have a personal connection to Daron Acemoglu as authors. David Hémous, for example, has conducted research with him several times 3, and Florian Scheuer completed his doctoral thesis at MIT under his supervision in 2010. We can both testify that Daron is an excellent mentor who generously shares his time and whose advice has always been very helpful.

1 See Smith (1776).

2 See Acemoglu, Aghion, Bursztyn, and Hémous (2012).

3 See, for example, Acemoglu, Aghion, Bursztyn, and Hémous (2012).

This year's Nobel Prize winners in economics show the influence of institutions on a country's prosperity. The three prizewinners have close ties to the University of Zurich, as UBS Foundation Professors David Hémous and Florian Scheuer outline in their article for 'Die Volkswirtschaft', an economic policy magazine by the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO).

This article by David Hémous and Florian Scheuer was originally published in 'Die Volkswirtschaft' on 8 November 2024 in German. Translated and edited for layout purposes by the UBS Center.

Adjusted for purchasing power, per capita income in Switzerland is 75 times higher than in the Democratic Republic of Congo, one of the poorest countries in the world. How can such extreme differences in prosperity levels be explained? And why is the economy of some countries growing while elsewhere it is stagnating or even shrinking? This question also occupied this year's winners of the “Alfred Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences”. In October 2024, the prize was awarded to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson (see box). These central questions have been occupying economics since the times of Adam Smith. As early as 1776, he was driven by these questions, to which he sought an answer in his magnum opus “The Wealth of Nations” 1. “Once you start thinking about it, it's hard to think about anything else,” said Robert Lucas, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1995. Traditionally, economics explains the different growth rates of countries by the fact that they invest different amounts in capital, education or technological innovation. This is because these investments boost the productivity of an economy and thus lead to higher income. However, this then raises another question: “Why” do some countries invest more than others? Or, in other words, what are the “fundamental” causes of economic growth?

Bibliography

Acemoglu, Daron (1998). Why Do New Technologies Complement Skills? Directed Technical Change and Wage Inequality, in: The Quarterly Journal of Economics 113.

Acemoglu, Daron, Philippe Aghion, Leonardo Bursztyn und David Hémous (2012). The Environment and Directed Technical Change, in: American Economic Review 102.

Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson und James Robinson (2001). The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation, in: American Economic Review 91.

Acemoglu, Daron und Simon Johnson (2023). Power and Progress: Our Thousand-year Struggle over Technology and Prosperity, Public Affairs.

Diamond, Jared (1997). Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies, Norton.

Lucas, Robert E. (1988). On the Mechanics of Economic Development, in: Journal of Monetary Economics 22.

Smith, Adam (1776). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.

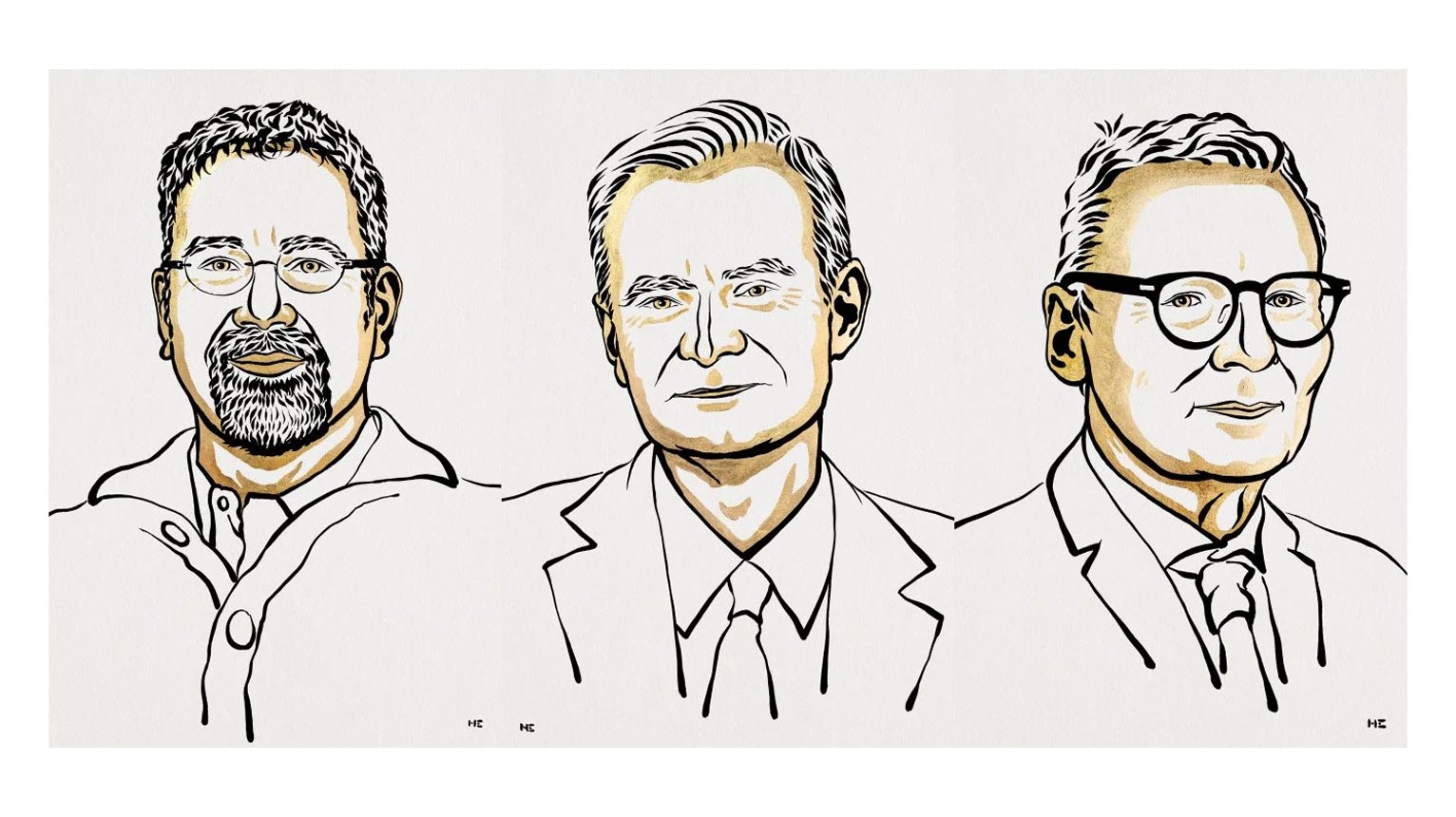

The three Nobel Prize winners

Kamer Daron Acemoğlu

The 57-year-old Turkish-American economist is a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). According to the economic literature database Repec, in 2015 he was the most cited author of the last ten years.

Simon Johnson

The 61-year-old British-American economist is a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management and former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund (2007–2008).

James Robinson

The 63-year-old British-American political scientist and economist teaches at the University of Chicago. He co-authored the book 'Why Nations Fail' with Daron Acemoglu.

Kamer Daron Acemoğlu

The 57-year-old Turkish-American economist is a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). According to the economic literature database Repec, in 2015 he was the most cited author of the last ten years.

Simon Johnson

The 61-year-old British-American economist is a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management and former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund (2007–2008).

Acemoglu Zurich Lecture

Contact

David Hémous received his PhD from Harvard University in 2012. He is a macroeconomist working on economic growth, climate change and inequality. His work highlights that innovation responds to economic incentives and that public policies should be designed taking this dependence into account. In particular, he has shown in the context of climate change policy that innovations in the car industry respond to gas prices and that global and regional climate policies should support clean innovation to efficiently reduce CO2 emissions. His work on technological change and income distribution shows that higher labor costs lead to more automation, and that the recent increase in labor income inequality and in the capital share can be explained by a secular increase in automation. He has also shown that innovation affects top income shares. He was awarded an ERC Starting Grant on 'Automation and Income Distribution – a Quantitative Assessment' and he received the 2022 'European Award for Researchers in Environmental Economics under the Age of Forty'.

Florian Scheuer received his PhD from MIT in 2010. He is interested in the policy implications of rising inequality, with a focus on tax policy. In particular, he has worked on incorporating important features of real-world labor markets into the design of optimal income and wealth taxes. These include economies with rent-seeking, superstar effects or an important entrepreneurial sector, frictional financial markets, as well as political constraints on tax policy and the resulting inequality. His work has been published in the American Economic Review, the Journal of Political Economy, the Quarterly Journal of Economics and the Review of Economic Studies, among other journals. In 2017, he received an ERC starting grant for his research on “Inequality - Public Policy and Political Economy.” Before joining Zurich, he was on the faculty at Stanford, held visiting positions at Harvard and UC Berkeley and was a National Fellow at the Hoover Institution. He is Co-Editor of Theoretical Economics and Member of the Board of Editors of the Review of Economic Studies. He is also a Co-Director of the working group on Macro Public Finance at the NBER. He has commented on tax policy in various US and Swiss media outlets.

David Hémous received his PhD from Harvard University in 2012. He is a macroeconomist working on economic growth, climate change and inequality. His work highlights that innovation responds to economic incentives and that public policies should be designed taking this dependence into account. In particular, he has shown in the context of climate change policy that innovations in the car industry respond to gas prices and that global and regional climate policies should support clean innovation to efficiently reduce CO2 emissions. His work on technological change and income distribution shows that higher labor costs lead to more automation, and that the recent increase in labor income inequality and in the capital share can be explained by a secular increase in automation. He has also shown that innovation affects top income shares. He was awarded an ERC Starting Grant on 'Automation and Income Distribution – a Quantitative Assessment' and he received the 2022 'European Award for Researchers in Environmental Economics under the Age of Forty'.

Florian Scheuer received his PhD from MIT in 2010. He is interested in the policy implications of rising inequality, with a focus on tax policy. In particular, he has worked on incorporating important features of real-world labor markets into the design of optimal income and wealth taxes. These include economies with rent-seeking, superstar effects or an important entrepreneurial sector, frictional financial markets, as well as political constraints on tax policy and the resulting inequality. His work has been published in the American Economic Review, the Journal of Political Economy, the Quarterly Journal of Economics and the Review of Economic Studies, among other journals. In 2017, he received an ERC starting grant for his research on “Inequality - Public Policy and Political Economy.” Before joining Zurich, he was on the faculty at Stanford, held visiting positions at Harvard and UC Berkeley and was a National Fellow at the Hoover Institution. He is Co-Editor of Theoretical Economics and Member of the Board of Editors of the Review of Economic Studies. He is also a Co-Director of the working group on Macro Public Finance at the NBER. He has commented on tax policy in various US and Swiss media outlets.