Jump directly to

Poverty reduction

The world is a better place thanks to the many people who work to make it so, states UBS Foundation Professor Dina Pomeranz in a NZZ guest commentary.

This guest commentary by Dina Pomeranz was originally published in German in NZZ on 11 November 2024. Translated and edited for layout purposes by the UBS Center.

It is often said that efforts to improve the world are naive or even hopeless. Wars, economic crises, natural disasters and other such news frequently dominate the headlines. But a look at the scientific evidence of the world's development in recent decades shows that, despite the many challenges, people's lives have improved dramatically in many ways. And this is thanks to the commitment of many people around the world.

The fight against poverty: a success story

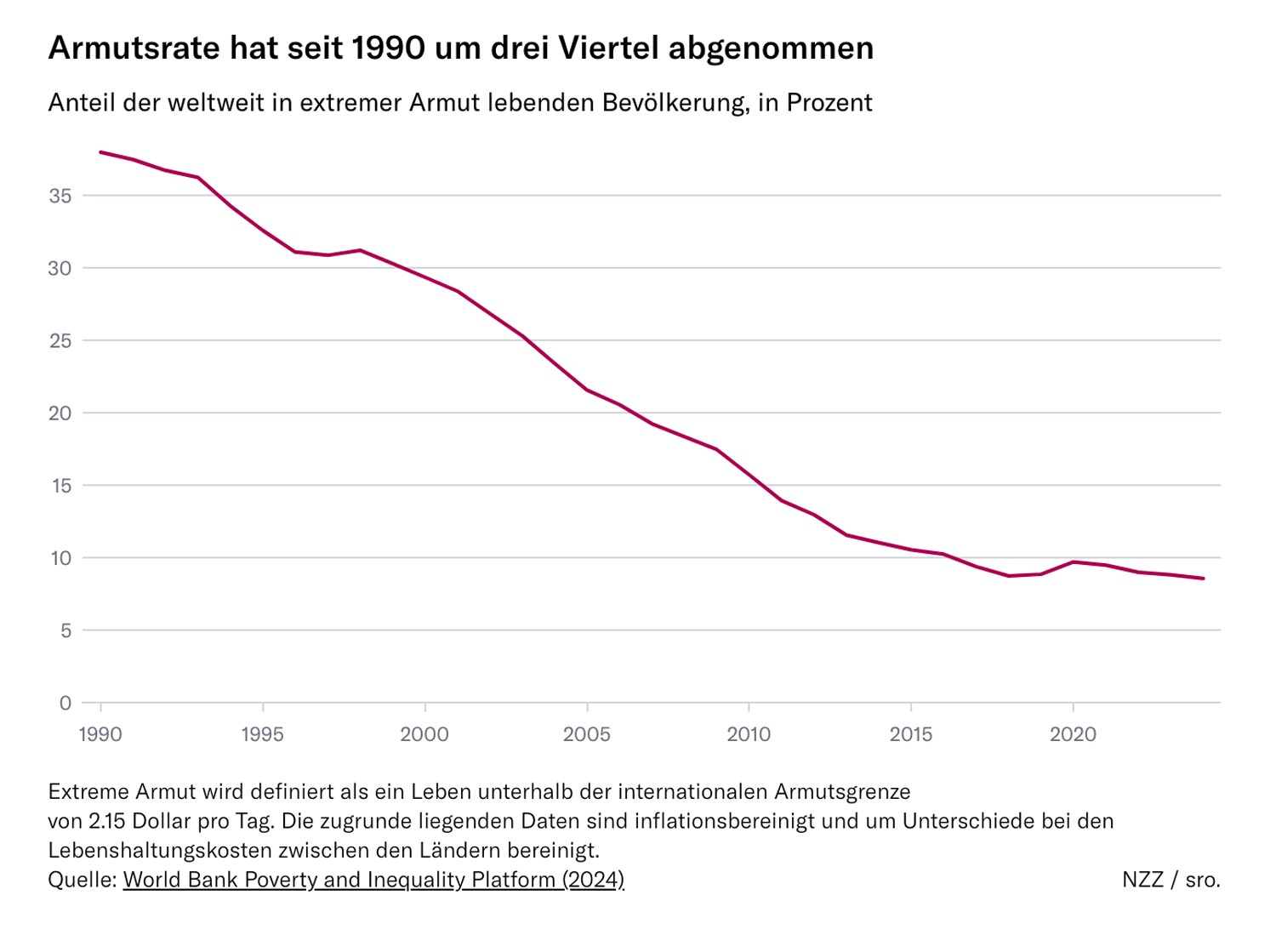

Our generation has seen the greatest global reduction in poverty in human history. Since 1990, global extreme poverty has fallen by three quarters from around 37 percent to 9 percent (in 1920 it was still around 80 percent). Extreme poverty is defined as a life with than 2.50 Swiss Francs per day (adjusted for price differences), but we see similar improvements at higher poverty lines, too. This is true not only for the share but also for the absolute number in poverty: despite the world population having increased more than sevenfold since 1820, a total of 240 million fewer people live in extreme poverty today than back then.

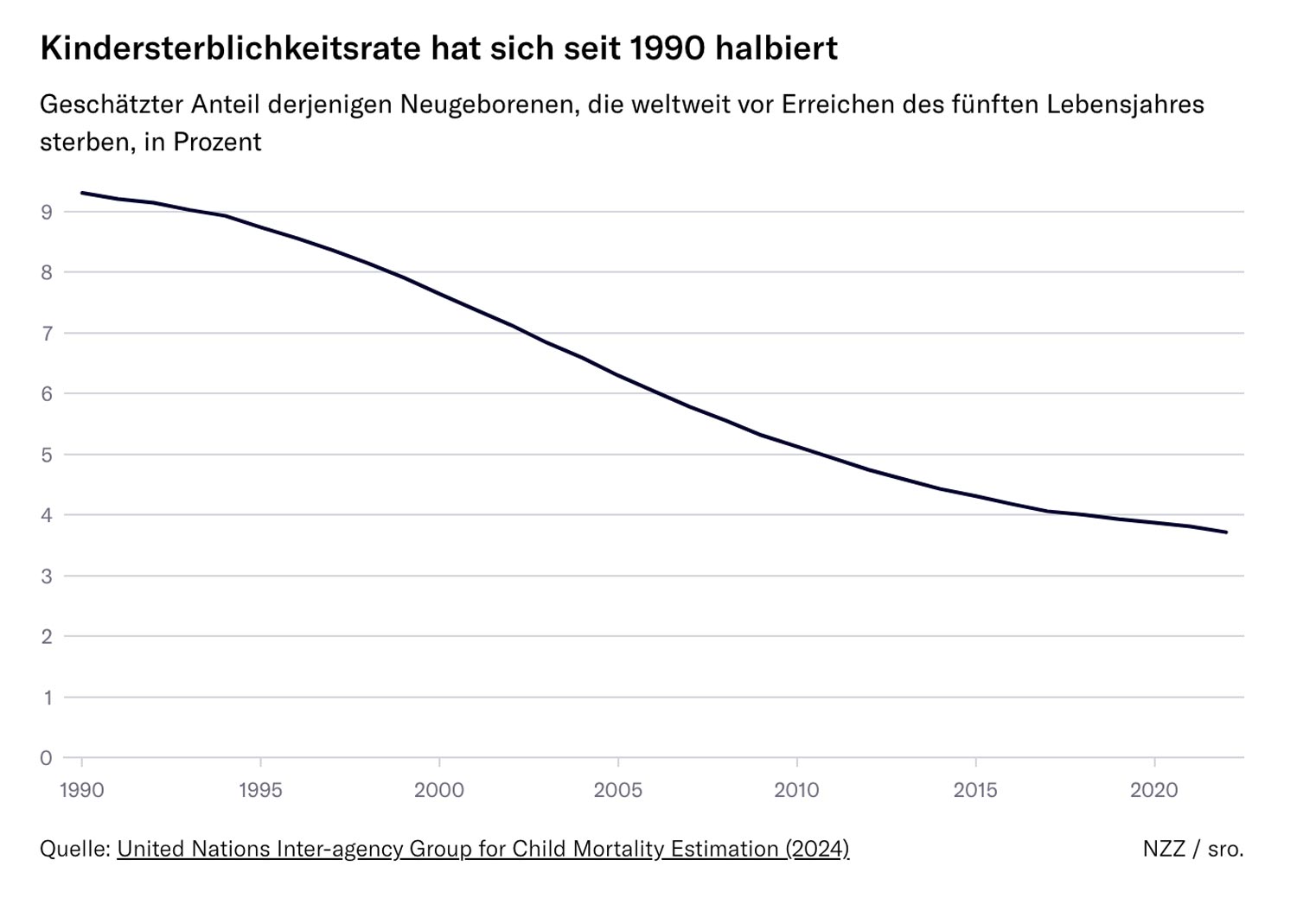

Another area in which humankind has made huge strides is healthcare. The decline in child mortality is one of the greatest revolutions in human history. The chart shows that while in 1800 more than four out of ten children still died before they reached the age of five, the mortality rate today is less than 0.4 out of 10 children. This goes to show how far we have come in combating preventable causes of death. Immunization programs, better medical care, and access to clean water and sanitation have contributed to these tremendous improvements. Accordingly, life expectancy is also increasing: in 1940, for example, the life expectancy in Switzerland was the same as that of present-day Ghana and lower than that of present-day Pakistan.

A common misunderstanding is that such a decline in mortality will lead to a “population explosion”. But the reality is more complex: the number of children worldwide is hardly growing anymore. This is because when child mortality decreases and thus the prospect of one’s own children surviving increases, most families have fewer children. Then why is the population still growing? The large younger generations that are already alive are growing up – but are themselves having fewer children. Countries are undergoing a demographic transition. In many countries, population growth has now slowed considerably, and some countries, including Switzerland, would actually shrink without immigration. The “population bomb” has been defused, and the world population is expected to remain stable or even decline in a few decades.

Behind all these statistical successes hide millions of transformed life realities. A decline in child and maternal mortality rates means less suffering and mourning for families. Less poverty also means less hunger, better health, less psychological stress and more access to education. All of this contributes to an improved quality of life, which more people than ever before are able to experience today. People who previously had to deal with survival on a daily basis now have the opportunity to pursue an education, express themselves and lead a self-determined life. This is also reflected in the increase in equality and liberal values. Globally, the proportion of women in parliament rose from just 9 percent in 1990 to 26 percent in 2023, and many countries have not only decriminalized homosexuality but have even legally recognized same-sex partnerships.

Progress cannot be taken for granted

It would be a serious mistake to conclude from the findings on these incredible improvements that progress is automatic and inevitable. Realities change thanks to the amazing efforts of people all over the world, whether in politics, in the development of new technologies, in medicine, by tapping into new markets, through social engagement, etc. International cooperation and development aid also play an important role. Thanks to improved methods and the availability of more data, we are able to showcase scientifically how development aid made it possible to provide millions of people with access to clean water, education and health services, and economic empowerment.

Nowadays, humanity is once again facing major challenges and risks: climate change, armed conflicts, the potential for further pandemics, and even artificial intelligence, to name just a few. While the proportion of people living in democracies has risen rapidly in the second half of the 20th century, reaching around 60 percent, this figure has stagnated or even fallen slightly since 2000. Autocratic tendencies are also on the rise in many so-called Western democracies.

These challenges make it clear that, alongside many successes, there have been and will continue to be setbacks. What matters is how we respond to these setbacks. In order to respond correctly, we need to analyze where we stand and where we came from. It is therefore worrying that many people are unaware of the extent to which human living conditions have improved. Surveys show that only around 10 percent of people know that global poverty has been halved. On the contrary, the majority even mistakenly believe that it doubled.

Such misinformation can lead to feelings of hopelessness, resignation and cynicism – and thus gives a boost to extremist political forces that promote the overthrow of all current structures. In the U.S., too, there is a great deal of unawareness of real trends. For example, millions of Americans mistakenly believe that in the last three years the economy has worsened and crime has increased, while the opposite is true.

Courage to be optimistic

The world is far from perfect. Humanity continuously faces major challenges. However, the outstanding historical successes in poverty reduction, health and education, as well as the overcoming of earlier crises such as the hole in the ozone layer or the AIDS epidemic, can show us that progress is not only possible, but has already taken place. Being aware of this can help us to maintain our courage and commit ourselves to fighting for further improvements.

The world is a better place thanks to the many people who work to make it so, states UBS Foundation Professor Dina Pomeranz in a NZZ guest commentary.

This guest commentary by Dina Pomeranz was originally published in German in NZZ on 11 November 2024. Translated and edited for layout purposes by the UBS Center.

It is often said that efforts to improve the world are naive or even hopeless. Wars, economic crises, natural disasters and other such news frequently dominate the headlines. But a look at the scientific evidence of the world's development in recent decades shows that, despite the many challenges, people's lives have improved dramatically in many ways. And this is thanks to the commitment of many people around the world.

NZZ Live

Is the world getting better and we just can't see it?

On November 26, Dina Pomeranz, Professor of Economics at the University of Zurich, was a guest at NZZ Live. Under the moderation of Damita Pressl, NZZ editor, she talked with experts about poverty, the role of development aid and how its impact can be measured. Presenting partner was the UZH Department of Economics.

Is the world getting better and we just can't see it?

On November 26, Dina Pomeranz, Professor of Economics at the University of Zurich, was a guest at NZZ Live. Under the moderation of Damita Pressl, NZZ editor, she talked with experts about poverty, the role of development aid and how its impact can be measured. Presenting partner was the UZH Department of Economics.

Contact

Dina Pomeranz's research focuses on public policies in developing countries, in particular in the areas of taxation, public procurement, firm development and the environment. Prior to joining the University of Zurich, she was an assistant professor at Harvard Business School, where she taught entrepreneurship for MBA students, and a Post-Doctoral Fellow at MIT's Poverty Action Lab.

Her work has been published in academic journals including the American Economic Review, the Quarterly Journal of Economics, the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, the Journal of Economic Development and the Journal of Human Resources. In 2017, she was awarded one of the prestigious grants from the European Research Council (ERC) for her research on tax evasion and the role of firm networks.

She is an affiliate professor at the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), the Bureau for Research and Economic Analysis of Development (BREAD) and the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and a member of the International Growth Centre (IGC). In 2018, she was elected to the Council of the European Economic Association (EEA), and in 2020 to the Board of Management of the International Institute of Public Finance (IIPF). She is a co-founder of the Graduate Applications International Network (GAIN), which supports prospective students from Africa in applying for graduate school in economics and related fields.

Professor Pomeranz also aims to contribute to the movement towards more evidence-based policy making, both in developing and economically more developed countries. With this goal in mind, she serves on the board or advisory board of a number of social enterprise ventures committed to translating research into practice, including Helvetas, Evidence Action, Policy Analytics, TamTam-Together Against Malaria and IDinsight. She has served as an expert witness to the Swiss parliament and is a member of the Federal Advisory Committee on International Cooperation.

Dina Pomeranz's research focuses on public policies in developing countries, in particular in the areas of taxation, public procurement, firm development and the environment. Prior to joining the University of Zurich, she was an assistant professor at Harvard Business School, where she taught entrepreneurship for MBA students, and a Post-Doctoral Fellow at MIT's Poverty Action Lab.

Her work has been published in academic journals including the American Economic Review, the Quarterly Journal of Economics, the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, the Journal of Economic Development and the Journal of Human Resources. In 2017, she was awarded one of the prestigious grants from the European Research Council (ERC) for her research on tax evasion and the role of firm networks.

She is an affiliate professor at the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), the Bureau for Research and Economic Analysis of Development (BREAD) and the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and a member of the International Growth Centre (IGC). In 2018, she was elected to the Council of the European Economic Association (EEA), and in 2020 to the Board of Management of the International Institute of Public Finance (IIPF). She is a co-founder of the Graduate Applications International Network (GAIN), which supports prospective students from Africa in applying for graduate school in economics and related fields.

Professor Pomeranz also aims to contribute to the movement towards more evidence-based policy making, both in developing and economically more developed countries. With this goal in mind, she serves on the board or advisory board of a number of social enterprise ventures committed to translating research into practice, including Helvetas, Evidence Action, Policy Analytics, TamTam-Together Against Malaria and IDinsight. She has served as an expert witness to the Swiss parliament and is a member of the Federal Advisory Committee on International Cooperation.